What is Greenwashing?

Well, here are two definitions by Greenpeace and the EU parliament:

“Greenwashing is a PR tactic used to make a company or product appear environmentally friendly, without meaningfully reducing its environmental impact.” – Greenpeace [1]

“The practice of giving a false impression of the environmental impact or benefits of a product, which can mislead consumers” – EU Parliament [2]

Coca Cola Life – Source: Greenpeace [1]

easyJet zero emission advert – Source: Greenpeace [1]

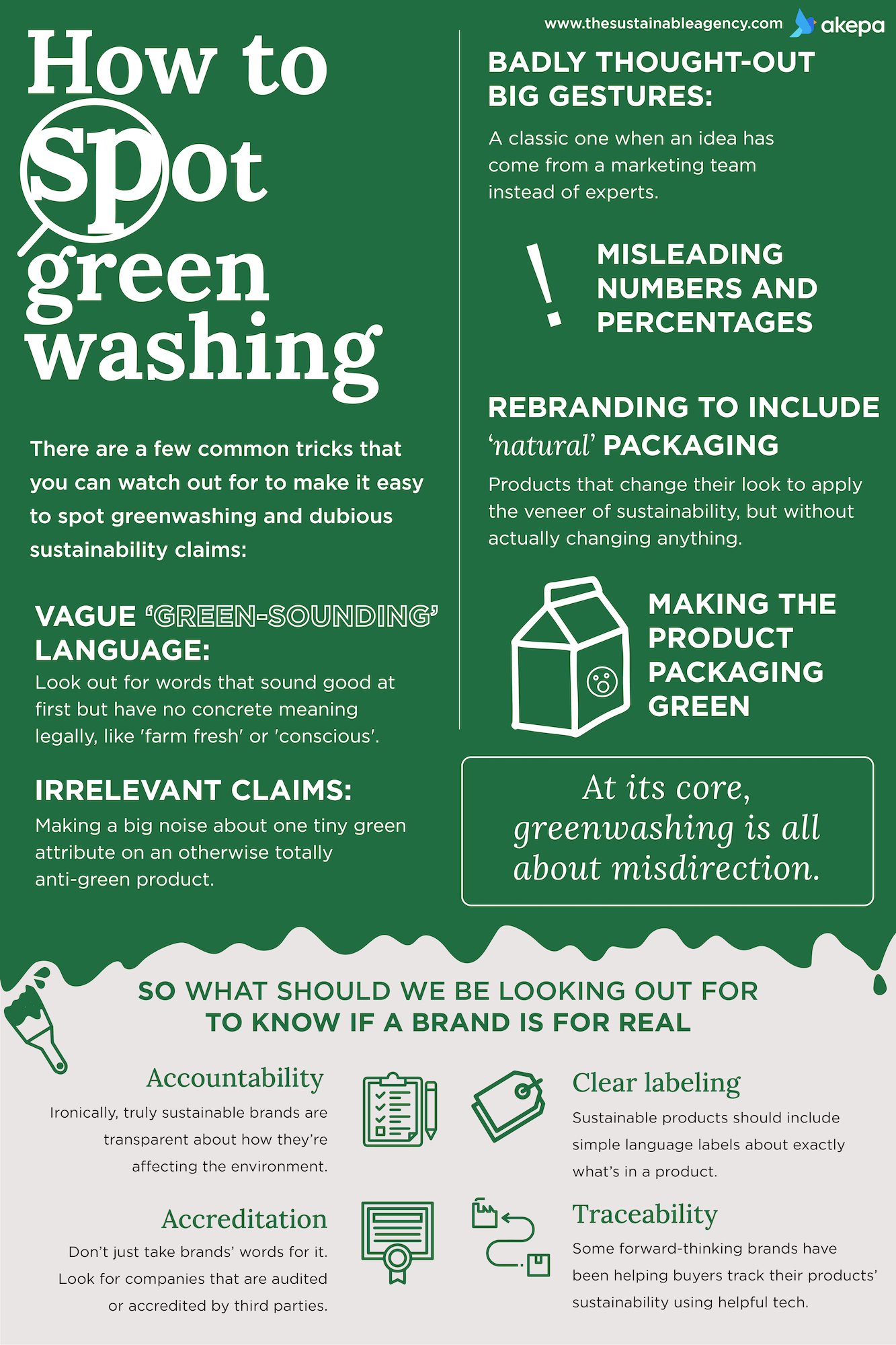

There are many forms of greenwashing, from claims that products are more environmentally sustainable than they actually are, to claims of not using harmful or dangerous ingredients in the formulation of products. [3]

The issue is these claims are often either misleading or incorrect. This can lead consumers into paying a premium for products they believe are more ecofriendly without actually being any different from a cheaper, ‘less ecofriendly’ product. [1]

By looking at greenwashing under the previous thought process, that a consumer is buying a product that is different than advertised, could be classed as a form of fraud. That’s to say, that consumers are, legally, being scammed by companies’ use of greenwashing tactics.

From Greenpeace’s website they give a variety of examples of greenwashing techniques they you may have seen or may currently know of companies using:

- “Token gestures. Promoting one ‘green’ feature, while ignoring other more important environmental issues. For example, a fast food company could promote a switch to recyclable paper straws, while still using meat suppliers responsible for burning down forests.

- Not being specific. Using very broad or poor definitions on purpose to cause misunderstanding. For example, using a recycling symbol on packaging without telling you which part is or can be recycled.

- No evidence to back up a claim. When a company wants you to take their word without sharing the proof behind their claim. So the claim can’t be checked or certified independently by someone else.

- Using green buzzwords or images. Adverts or packaging with lots of natural scenes, or images like trees and leaves. Or buzzwords that are meaningless without explanation, like ‘non-toxic’, ‘all natural’, ‘eco conscious’ and ‘chemical-free’. This also includes putting a green label onto a product or company that’s environmentally harmful anyway.

- Carbon offsetting. A way to try to make up for the pollution you cause, instead of trying to reduce it. Usually, it’s done by paying others to reduce carbon emissions or take carbon out of the atmosphere. It’s greenwashing because it still means lots of carbon goes into the atmosphere.

- Redundant claims. This is when the claim is not needed. For example, a company advertising a product as vegan or plant-based, when it would be anyway.” [1]

It’s probably not hard to find examples of these in your everyday life, the most iconic being redundant claims; It’s funny to read that a tube of toothpaste is vegan, why wouldn’t it be?

Source: The Sustainable Agency [4]

Turkish bus with government recyling promotions alongside goverment funded free coal – Source: Wikipedia [6]

However at least in the EU there is a strong push to eliminate or at least greatly reduce greenwashing. This will be through banning the main forms of greenwashing, such as stopping the use of generic and unverifiable claims on products. [2]

As well as this there are ways that companies can show that they are indeed reducing their environmental impact, such as through an ‘Environmental Product Declaration’ or EPD. These are a “standardised, third-party verified statement that provides transparent and credible information about any type of product’s environmental performance throughout its life cycle”. [5]

The use of EPDs will allow consumers to understand much more easily the impact their purchases will have on the environment. It will allow consumers to compare two products and to understand their individual environmental impact. Then to be able to confidently answer the question of whether it’s worth paying a premium (not always the more expensive product but sustainability unfortunately costs more usually) to buy a more sustainable product.

Get in Touch with Us!

We’d love to hear from you. Whether you have feedback, suggestions, or want to share insights related to sustainability and environmental truth, your voice matters. At Earth Athenaeum, we believe in open dialogue and collaboration to uncover and explore the realities behind green initiatives and corporate claims.

If you have questions, ideas, or simply want to connect, feel free to reach out — we’re here to engage, listen, and learn together.

Reference List And Further Reading

[1] – Das L. Greenwashing: How to spot fake green claims [Internet]. Greenpeace UK. 2022. Available from: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/news/what-is-greenwashing/

[2] – European Parliament. Stopping greenwashing: How the EU Regulates Green Claims [Internet]. European Parliament. 2024. Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20240111STO16722/stopping-greenwashing-how-the-eu-regulates-green-claims

[3] – McCroskey K. Target Cosmetics Labeled “Target Clean” Are Not as Clean as Advertised, Class Action Alleges [Internet]. www.classaction.org. 2023. Available from: https://www.classaction.org/blog/target-cosmetics-labeled-target-clean-are-not-as-clean-as-advertised-class-action-alleges

[4] – Peel-Yates V. Greenwashing examples from 2020 & 2021 | Worst products & brands [Internet]. The Sustainable Agency. akepa; 2021. Available from: https://thesustainableagency.com/blog/greenwashing-examples/

[5] – EPD Library | EPD International [Internet]. www.environdec.com. Available from: https://www.environdec.com/library

[6]Wikipedia Contributors. Greenwashing [Internet]. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation; 2019. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenwashing